The Goal is often touted as one of the most important business books of all time, yet many of the key principles are not widely applied in business process management. In The Goal, Eliyahu Goldratt describes his Theory of Constraints through a fable where the protagonist, a manufacturing plant manager named Alex is guided through the recovery of his plant by his old physics professor turned business consultant, Jonah. Jonah appears throughout the story to teach Alex in Socratic style to solve the underlying problems of his plant’s operations. In the end of course, the plant is saved and Alex is promoted.

The Goal is often touted as one of the most important business books of all time, yet many of the key principles are not widely applied in business process management. In The Goal, Eliyahu Goldratt describes his Theory of Constraints through a fable where the protagonist, a manufacturing plant manager named Alex is guided through the recovery of his plant by his old physics professor turned business consultant, Jonah. Jonah appears throughout the story to teach Alex in Socratic style to solve the underlying problems of his plant’s operations. In the end of course, the plant is saved and Alex is promoted.

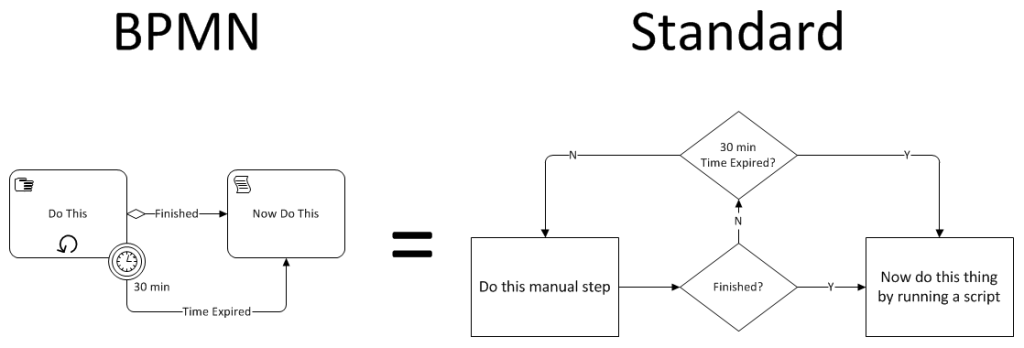

The underlying principles of Constraint Theory are key to analyzing any process. But, it often takes a bit of a leap to apply lessons from manufacturing process to the less tangible world of business transaction based processes. In manufacturing, the process is visual. Inventory is physical. Throughput can be counted in widgets produced and sold. But in business processes, these things can be difficult to identify, see and count. I believe here in lies the rub for Jonah (and Lean for that matter).

With Jonah’s guidance, Alex comes to realize that the management metrics he uses to manage daily operations are all wrong. He discovers that the goal is not to improve efficiency, increase resource utilization or control costs, which are some of his current measures. The goal of any business is to MAKE MONEY…period. Therefore, all metrics must be in the context of contribution to that overall goal for the company. Also, Alex’s metrics were all focused on optimizing individual parts of the system; the sub-processes. Metrics that encourage optimizing sub-processes can be detrimental to the performance of the larger system. So, measurement must be focused on the performance of the system.

I struggled with two foundational problems when thinking about how to apply the Constraint Theory principles in my work. First, I’m almost never working on a production process that directly affects sales. For example, how does one equate the process of approving and paying employee expense reports to The Goal of making money? Second, Jonah focuses Alex on optimizing the whole system above individual processes. But, I’m never working at the “plant” level, always at the sub-system process level. Not sure what Jonah would say about these two challenges but here’s how I wrap my brain around them.

I redefine the goal in the context of the process I’m focused on. Think of the process itself as a stand alone business. Using the expense report process as an example. If the expense report process were a business, then the business would presumably be paid for accurately reimbursing employees for expenses. So, again as a business, reimbursing employees is what makes money so, the goal in this case is to accurately reimburse employees.

By putting the goal in context this way, you address both challenges. First, you can now show impact on ‘sales’ of the process. Second, you can now work at a system level since the scope of the system is now any process or sub-process that supports the activity of accurately reimbursing employees (the goal). Maybe this is painfully obvious to most but it helps me define what I’m working on at my level.